Harvestmen Lat. “Opiliones“

The Opiliones /oʊˌpɪliˈoʊniːz/ or /ɒˌpɪliˈoʊnɛz/ (formerly Phalangida) are an order of arachnids colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters or daddy longlegs. As of April 2017, over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered worldwide, although the total number of extant species may exceed 10,000. The order Opiliones includes five suborders: Cyphophthalmi, Eupnoi, Dyspnoi, Laniatores, and the recently named Tetrophthalmi.

Description

The Opiliones are known for having exceptionally long legs relative to their body size; however, some species are short-legged. As in all Arachnida, the body in the Opiliones has two tagmata, the anterior cephalothorax or prosoma, and the posterior 10-segmented abdomen or opisthosoma. The most easily discernible difference between harvestmen and spiders is that in harvestmen, the connection between the cephalothorax and abdomen is broad, so that the body appears to be a single oval structure. Other differences include the fact that Opiliones have no venom glands in their chelicerae and thus pose no danger to humans. They also have no silk glands and therefore do not build webs. In some highly derived species, the first five abdominal segments are fused into a dorsal shield called the scutum, which in most such species is fused with the carapace. Some such Opiliones only have this shield in the males. In some species, the two posterior abdominal segments are reduced. Some of them are divided medially on the surface to form two plates beside each other. The second pair of legs is longer than the others and function as antennae or feelers. In short-legged species, this may not be obvious. The feeding apparatus (stomotheca) differs from most arachnids in that Opiliones can swallow chunks of solid food, not only liquids. The stomotheca is formed by extensions of the coxae of the pedipalps and the first pair of legs. Most Opiliones, except for Cyphophthalmi, have long been thought to have a single pair of camera-type eyes in the middle of the head, oriented sideways. Eyes in Cyphophthalmi, when present, are located laterally, near the ozopores. A 305-million-year-old fossilized harvestman with two pairs of eyes was reported in 2014. This find suggested that the eyes in Cyphophthalmi are not homologous to the eyes of other harvestmen. Many cave-adapted species are eyeless, such as the Brazilian Caecobunus termitarum (Grassatores) from termite nests, Giupponia chagasi (Gonyleptidae) from caves, most species of Cyphophthalmi, and all species of the Guasiniidae. However, recent work studying the embryonic development of the species Phalangium opilio and some Laniatores revealed that harvestman in addition to a pair of median eyes also have two sets of vestigial eyes: one median pair (homologous to those of horseshoe crabs and sea spiders), and one lateral pair (homologous to facetted eyes of horseshoe crabs and insects). This discovery suggests that the neuroanatomy of harvestmen is more primitive than derived arachnid groups, like spiders and scorpions. It also showed that the four-eyed fossil harvestman previously discovered is most likely a member of the suborder Eupnoi (true daddy-longlegs).

Harvestmen have a pair of prosomatic defensive scent glands (ozopores) that secrete a peculiar-smelling fluid when disturbed. In some species, the fluid contains noxious quinones. They do not have book lungs, and breathe through tracheae. A pair of spiracles is located between the base of the fourth pair of legs and the abdomen, with one opening on each side. In more active species, spiracles are also found upon the tibia of the legs. They have a gonopore on the ventral cephalothorax, and the copulation is direct as male Opiliones have a penis, unlike other arachnids. All species lay eggs. Typical body length does not exceed 7 mm (0.28 in), and some species are smaller than 1 mm, although the largest known species, Trogulus torosus (Trogulidae), grows as long as 22 mm (0.87 in). The leg span of many species is much greater than the body length and sometimes exceeds 160 mm (6.3 in) and to 340 mm (13 in) in Southeast Asia. Most species live for a year.

Behavior

Many species are omnivorous, eating primarily small insects and all kinds of plant material and fungi. Some are scavengers, feeding upon dead organisms, bird dung, and other fecal material. Such a broad range is unusual in arachnids, which are typically pure predators. Most hunting harvestmen ambush their prey, although active hunting is also found. Because their eyes cannot form images, they use their second pair of legs as antennae to explore their environment. Unlike most other arachnids, harvestmen do not have a sucking stomach or a filtering mechanism. Rather, they ingest small particles of their food, thus making them vulnerable to internal parasites such as gregarines. Although parthenogenetic species do occur, most harvestmen reproduce sexually. Except from small fossorial species in the suborder Cyphophthalmi, where the males deposit a spermatophore, mating involves direct copulation. The females store the sperm, which is aflagellate and immobile, at the tip of her ovipositor. The eggs are fertilized during oviposition. The males of some species offer a secretion (nuptial gift) from their chelicerae to the female before copulation. Sometimes, the male guards the female after copulation, and in many species, the males defend territories. In some species, males also exhibit post-copulatory behavior in which the male specifically seeks out and shakes the female’s sensory leg. This is believed to entice the female into mating a second time. The female lays her eggs shortly after mating to several months later. Some species build nests for this purpose. A unique feature of harvestmen is that some species practice parental care, in which the male is solely responsible for guarding the eggs resulting from multiple partners, often against egg-eating females, and cleaning the eggs regularly. Paternal care has evolved at least three times independently: once in the clade Progonyleptoidellinae + Caelopyginae, once in the Gonyleptinae, and once in the Heteropachylinae. Maternal care in opiliones probably evolved due to natural selection, while paternal care appears to be the result of sexual selection. Depending on circumstances such as temperature, the eggs may hatch at any time after the first 20 days, up to about half a year after being laid. Harvestmen variously pass through four to eight nymphal instars to reach maturity, with most known species having six instars. Most species are nocturnal and colored in hues of brown, although a number of diurnal species are known, some of which have vivid patterns in yellow, green, and black with varied reddish and blackish mottling and reticulation. Many species of harvestmen easily tolerate members of their own species, with aggregations of many individuals often found at protected sites near water. These aggregations may number 200 individuals in the Laniatores, and more than 70,000 in certain Eupnoi. Gregarious behavior is likely a strategy against climatic odds, but also against predators, combining the effect of scent secretions, and reducing the probability of any particular individual being eaten. Harvestmen clean their legs after eating by drawing each leg in turn through their jaws.

Antipredator defences

Predators of harvestmen include a variety of animals, including some mammals, amphibians, and other arachnids like spiders and scorpions. Opiliones display a variety of primary and secondary defences against predation, ranging from morphological traits such as body armour to behavioral responses to chemical secretions. Some of these defences have been attributed and restricted to specific groups of harvestmen.

Endangered status

All troglobitic species (of all animal taxa) are considered to be at least threatened in Brazil. Four species of Opiliones are on the Brazilian national list of endangered species, all of them cave-dwelling: Giupponia chagasi, Iandumoema uai, Pachylospeleus strinatii and Spaeleoleptes spaeleus. Several Opiliones in Argentina appear to be vulnerable, if not endangered. These include Pachyloidellus fulvigranulatus, which is found only on top of Cerro Uritorco, the highest peak in the Sierras Chicas chain (provincia de Cordoba) and Pachyloides borellii is in rainforest patches in northwest Argentina which are in an area being dramatically destroyed by humans. The cave-living Picunchenops spelaeus is apparently endangered through human action. So far, no harvestman has been included in any kind of a Red List in Argentina, so they receive no protection. Maiorerus randoi has only been found in one cave in the Canary Islands. It is included in the Catálogo Nacional de especies amenazadas (National catalog of threatened species) from the Spanish government. Texella reddelli and Texella reyesi are listed as endangered species in the United States. Both are from caves in central Texas. Texella cokendolpheri from a cave in central Texas and Calicina minor, Microcina edgewoodensis, Microcina homi, Microcina jungi, Microcina leei, Microcina lumi, and Microcina tiburona from around springs and other restricted habitats of central California are being considered for listing as endangered species, but as yet receive no protection.

Misconception

An urban legend claims that the harvestman is the most venomous animal in the world; however, it possesses fangs too short or a mouth too round and small to bite a human, rendering it harmless (the same myth applies to Pholcus phalangioides and the crane fly, which are both also called a “daddy longlegs”). None of the known species of harvestmen have venom glands; their chelicerae are not hollowed fangs but grasping claws that are typically very small and not strong enough to break human skin.

Research

Harvestmen are a scientifically neglected group. Description of new taxa has always been dependent on the activity of a few dedicated taxonomists. Carl Friedrich Roewer described about a third (2,260) of today’s known species from the 1910s to the 1950s, and published the landmark systematic work Die Weberknechte der Erde (Harvestmen of the World) in 1923, with descriptions of all species known to that time. Other important taxonomists in this field include:

Pierre André Latreille (18th century) Carl Ludwig Koch, Maximilian Perty (1830s–1850s) L. Koch, Tord Tamerlan Teodor Thorell (1860s–1870s) Eugène Simon, William Sørensen (1880s–1890s) James C. Cokendolpher, Raymond Forster, Clarence and Marie Goodnight, Jürgen Gruber, Reginald Frederick Lawrence, Jochen Martens, Cândido Firmino de Mello-Leitão (20th century) Gonzalo Giribet, Adriano Brilhante Kury, Tone Novak (21st century) Since the 1990s, study of the biology and ecology of harvestmen has intensified, especially in South America. Early work on the developmental biology of Opiliones from the mid-20th century was resurrected by Prashant P. Sharma, who established Phalangium opilio as a model system for the study of arachnid comparative genomics and evolutionary-developmental biology.

Phylogeny

Harvestmen are ancient arachnids. Fossils from the Devonian Rhynie chert, 410 million years ago, already show characteristics like tracheae and sexual organs, indicating that the group has lived on land since that time. Despite being similar in appearance to, and often confused with, spiders, they are probably closely related to the scorpions, pseudoscorpions, and solifuges; these four orders form the clade Dromopoda. The Opiliones have remained almost unchanged morphologically over a long period. Indeed, one species discovered in China, Mesobunus martensi, fossilized by fine-grained volcanic ash around 165 million years ago, is hardly discernible from modern-day harvestmen and has been placed in the extant family Sclerosomatidae.

Systematics

The interfamilial relationships within Opiliones are not yet fully resolved, although significant strides have been made in recent years to determine these relationships. The following list is a compilation of interfamilial relationships recovered from several recent phylogenetic studies, although the placement and even monophyly of several taxa are still in question.

The family Stygophalangiidae (one species, Stygophalangium karamani) from underground waters in North Macedonia is sometimes misplaced in the Phalangioidea. It is not a harvestman.

Fossil record

Despite their long history, few harvestman fossils are known. This is mainly due to their delicate body structure and terrestrial habitat, making them unlikely to be found in sediments. As a consequence, most known fossils have been preserved within amber. The oldest known harvestman, from the 410-million-year-old Devonian Rhynie chert, displayed almost all the characteristics of modern species, placing the origin of harvestmen in the Silurian, or even earlier. A recent molecular study of Opiliones, however, dated the origin of the order at about 473 million years ago (Mya), during the Ordovician. No fossils of the Cyphophthalmi or Laniatores much older than 50 million years are known, despite the former presenting a basal clade, and the latter having probably diverged from the Dyspnoi more than 300 Mya. Naturally, most finds are from comparatively recent times. More than 20 fossil species are known from the Cenozoic, three from the Mesozoic, and at least seven from the Paleozoic.

Etymology

The Swedish naturalist and arachnologist Carl Jakob Sundevall (1801–1875) honored the naturalist Martin Lister (1638–1712) by adopting Lister’s term Opiliones for this order, from Latin ōpiliō (“shepherd”), because these arachnids were known in Lister’s days as “shepherd spiders”; Lister characterized three species from England (although not formally describing them, being a pre-Linnaean work). In England, the Opiliones are often called “harvestmen” or “harvest spiders”. Folk-etymological explanations for this are numerous, such as that they appear during harvest season, or because of a superstitious belief that if one is killed there will be a bad harvest that year, but these are unfounded. More likely, as in other European languages which call them a word meaning “cutter” or “scyther”, the original explanation is that their oddly shaped legs look like tiny sickles or scythes. The alternative name “shepherd spiders” is sometimes attributed to the assumption that Englishmen knew of the shepherds in the Landes region of France who traditionally used stilts to better observe their wandering flocks from a distance, and so were reminded of them by the long-legged arachnid, but is much more likely just an extension of this agricultural imagery, with the farmer’s implement changed to a shepherd’s crook rather than a reaping tool. Compare similar developments in the Dutch words for Opiliones: hooiwagen (literally meaning “hay-wagon”) and in southern dialects koewachter (literally “cowherd”, one who herds cattle). English speakers may colloquially refer to species of Opiliones as “daddy longlegs” or “granddaddy longlegs”. However, this name is also used for two other distantly related groups of arthropods: the crane flies of the superfamily Tipuloidea, as well as the cellar spiders of the family Pholcidae (which may be distinguished as “daddy long-leg spiders”), because of their similar appearance.

External links

Media related to Opiliones at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Opiliones at Wikispecies Adriano Kury: National Museum of Rio de Janeiro Classification of Opiliones—A synoptic taxonomic arrangement of the order Opiliones, down to family-group level, including some photos of the families Harvestman: Order Opiliones—Diagnostic photographs and information on North American harvestmen Harvestman: Order Opiliones—Diagnostic photographs and information on European harvestmen University of Aberdeen: The Rhynie Chert Harvestmen (fossils) Joel Hallan’s Biology Catalog (Archive only before 2017

Ancestry Graph

Further Information

„Harvestmen“ on iNaturalist.org

Copyright

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Opiliones the free encyclopedia Wikipedia which is released under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License). On Wikipedia a list of authors is available.

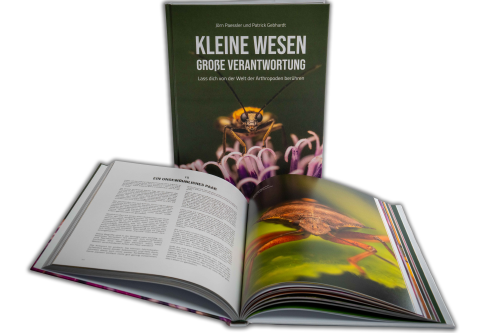

Little beings in print

Order our calendars and books today!

Compiled with love. Printed sustainably. Experience our little beings even more vividly in print. All our publications are available for a small donation.