Aphidoidea Lat. “Aphidoidea“

Aphids, also known as plant lice and in Britain and the Commonwealth as greenflies, blackflies, or whiteflies (not to be confused with “jumping plant lice” or true whiteflies), are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Many species are green, but other commonly occurring species may be white and wooly, brown, or black. Aphids are among the most destructive insect pests on cultivated plants in temperate regions. They are capable of extremely rapid increase…

Hierarchy

Etymology

The name aphid is from Carl Linnaeus’s modern Latin, most likely from misreading the Middle Greek κόρῐς, koris, ‘bug’ as αφῐς, aphis.

Distribution

Aphids are distributed worldwide, but are most common in temperate zones. In contrast to many taxa, aphid species diversity is much lower in the tropics than in the temperate zones. They can migrate great distances, mainly through passive dispersal by winds. Winged aphids may also rise up in the day as high as 600 m where they are transported by strong winds. For example, the currant-lettuce aphid, Nasonovia ribisnigri, is believed to have spread from New Zealand to Tasmania around 2004 through easterly winds. Aphids have also been spread by human transportation of infested plant materials, making some species nearly cosmopolitan in their distribution.

Anatomy

Most aphids have soft bodies, which may be green, black, brown, pink, or almost colorless. Aphids have antennae with two short, broad basal segments and up to four slender terminal segments. They have a pair of compound eyes, with an ocular tubercle behind and above each eye, made up of three lenses called triommatidia. They feed on sap and plant fluids using piercing-sucking mouthparts called stylets, enclosed in a sheath called a rostrum, which is formed from modifications of the mandible and maxilla of the insect mouthparts. They have long, thin legs with two-jointed, two-clawed tarsi. The majority of aphids are wingless, but winged forms are produced at certain times of year in many species. Most aphids have a pair of cornicles (siphunculi), abdominal tubes on the dorsal surface of their fifth abdominal segment, through which they exude droplets of a quick-hardening defensive fluid containing triacylglycerols, called cornicle wax. Other defensive compounds can also be produced by some species. Aphids have a tail-like protrusion called a cauda above their rectal apertures. They have lost their Malpighian tubules. When host plant quality becomes poor or conditions become crowded, some aphid species produce winged offspring (alates) that can disperse to other food sources. The mouthparts or eyes can be small or missing in some species and forms.

Diet

Many aphid species are monophagous (that is, they feed on only one plant species). Others, like the green peach aphid, feed on hundreds of plant species across many families. About 10% of species feed on different plants at different times of the year. A new host plant is chosen by a winged adult by using visual cues, followed by olfaction using the antennae; if the plant smells right, the next action is probing the surface upon landing. The stylus is inserted and saliva secreted, the sap is sampled, the xylem may be tasted and finally, the phloem is tested. Aphid saliva may inhibit phloem-sealing mechanisms and has pectinases that ease penetration. Non-host plants can be rejected at any stage of the probe, but the transfer of viruses occurs early in the investigation process, at the time of the introduction of the saliva, so non-host plants can become infected. Aphids usually feed passively on sap of phloem vessels in plants, as do many other hemipterans such as scale insects and cicadas. Once a phloem vessel is punctured, the sap, which is under pressure, is forced into the aphid’s food canal. Occasionally, aphids also ingest xylem sap, which is a more dilute diet than phloem sap as the concentrations of sugars and amino acids are 1% of those in the phloem. Xylem sap is under negative hydrostatic pressure and requires active sucking, suggesting an important role in aphid physiology. As xylem sap ingestion has been observed following a dehydration period, aphids are thought to consume xylem sap to replenish their water balance; the consumption of the dilute sap of xylem permitting aphids to rehydrate. However, recent data showed aphids consume more xylem sap than expected and they notably do so when they are not dehydrated and when their fecundity decreases. This suggests aphids, and potentially, all the phloem-sap feeding species of the order Hemiptera, consume xylem sap for reasons other than replenishing water balance. Although aphids passively take in phloem sap, which is under pressure, they can also draw fluid at negative or atmospheric pressure using the cibarial-pharyngeal pump mechanism present in their head. Xylem sap consumption may be related to osmoregulation. High osmotic pressure in the stomach, caused by high sucrose concentration, can lead to water transfer from the hemolymph to the stomach, thus resulting in hyperosmotic stress and eventually to the death of the insect. Aphids avoid this fate by osmoregulating through several processes. Sucrose concentration is directly reduced by assimilating sucrose toward metabolism and by synthesizing oligosaccharides from several sucrose molecules, thus reducing the solute concentration and consequently the osmotic pressure. Oligosaccharides are then excreted through honeydew, explaining its high sugar concentrations, which can then be used by other animals such as ants. Furthermore, water is transferred from the hindgut, where osmotic pressure has already been reduced, to the stomach to dilute stomach content. Eventually, aphids consume xylem sap to dilute the stomach osmotic pressure. All these processes function synergetically, and enable aphids to feed on high-sucrose-concentration plant sap, as well as to adapt to varying sucrose concentrations. Plant sap is an unbalanced diet for aphids, as it lacks essential amino acids, which aphids, like all animals, cannot synthesise, and possesses a high osmotic pressure due to its high sucrose concentration. Essential amino acids are provided to aphids by bacterial endosymbionts, harboured in special cells, bacteriocytes. These symbionts recycle glutamate, a metabolic waste of their host, into essential amino acids.

Carotenoids and photoheterotrophy

Some species of aphids have acquired the ability to synthesise red carotenoids by horizontal gene transfer from fungi. They are the only animals other than two-spotted spider mites and the oriental hornet with this capability. Using their carotenoids, aphids may well be able to absorb solar energy and convert it to a form that their cells can use, ATP. This is the only known example of photoheterotrophy in animals. The carotene pigments in aphids form a layer close to the surface of the cuticle, ideally placed to absorb sunlight. The excited carotenoids seem to reduce NAD to NADH which is oxidized in the mitochondria for energy.

Reproduction

The simplest reproductive strategy is for an aphid to have a single host all year round. On this it may alternate between sexual and asexual generations (holocyclic) or alternatively, all young may be produced by parthenogenesis, eggs never being laid (anholocyclic). Some species can have both holocyclic and anholocyclic populations under different circumstances but no known aphid species reproduce solely by sexual means. The alternation of sexual and asexual generations may have evolved repeatedly. However, aphid reproduction is often more complex than this and involves migration between different host plants. In about 10% of species, there is an alternation between woody (primary) hosts on which the aphids overwinter and herbaceous (secondary) host plants, where they reproduce abundantly in the summer. A few species can produce a soldier caste, other species show extensive polyphenism under different environmental conditions and some can control the sex ratio of their offspring depending on external factors. When a typical sophisticated reproductive strategy is used, only females are present in the population at the beginning of the seasonal cycle (although a few species of aphids have been found to have both male and female sexes at this time). The overwintering eggs that hatch in the spring result in females, called fundatrices (stem mothers). Reproduction typically does not involve males (parthenogenesis) and results in a live birth (viviparity). The live young are produced by pseudoplacental viviparity, which is the development of eggs, deficient in the yolk, the embryos fed by a tissue acting as a placenta. The young emerge from the mother soon after hatching. Eggs are parthenogenetically produced without meiosis and the offspring are clonal to their mother, so they are all female (thelytoky). The embryos develop within the mothers’ ovarioles, which then give birth to live (already hatched) first-instar female nymphs. As the eggs begin to develop immediately after ovulation, an adult female can house developing female nymphs which already have parthenogenetically developing embryos inside them (i.e. they are born pregnant). This telescoping of generations enables aphids to increase in number with great rapidity. The offspring resemble their parent in every way except size. Thus, a female’s diet can affect the body size and birth rate of more than two generations (daughters and granddaughters). This process repeats itself throughout the summer, producing multiple generations that typically live 20 to 40 days. For example, some species of cabbage aphids (like Brevicoryne brassicae) can produce up to 41 generations of females in a season. Thus, one female hatched in spring can theoretically produce billions of descendants, were they all to survive.

In autumn, aphids reproduce sexually and lay eggs. Environmental factors such as a change in photoperiod and temperature, or perhaps a lower food quantity or quality, causes females to parthenogenetically produce sexual females and males. The males are genetically identical to their mothers except that, with the aphids’ X0 sex-determination system, they have one fewer sex chromosome. These sexual aphids may lack wings or even mouthparts. Sexual females and males mate, and females lay eggs that develop outside the mother. The eggs survive the winter and hatch into winged (alate) or wingless females the following spring. This occurs in, for example, the life cycle of the rose aphid (Macrosiphum rosae), which may be considered typical of the family. However, in warm environments, such as in the tropics or a greenhouse, aphids may go on reproducing asexually for many years.

Aphids reproducing asexually by parthenogenesis can have genetically identical winged and non-winged female progeny. Control is complex; some aphids alternate during their life-cycles between genetic control (polymorphism) and environmental control (polyphenism) of production of winged or wingless forms. Winged progeny tend to be produced more abundantly under unfavorable or stressful conditions. Some species produce winged progeny in response to low food quality or quantity. e.g. when a host plant is starting to senesce. The winged females migrate to start new colonies on a new host plant. For example, the apple aphid (Aphis pomi), after producing many generations of wingless females gives rise to winged forms that fly to other branches or trees of its typical food plant. Aphids that are attacked by ladybugs, lacewings, parasitoid wasps, or other predators can change the dynamics of their progeny production. When aphids are attacked by these predators, alarm pheromones, in particular beta-farnesene, are released from the cornicles. These alarm pheromones cause several behavioral modifications that, depending on the aphid species, can include walking away and dropping off the host plant. Additionally, alarm pheromone perception can induce the aphids to produce winged progeny that can leave the host plant in search of a safer feeding site. Viral infections, which can be extremely harmful to aphids, can also lead to the production of winged offspring. For example, Densovirus infection has a negative impact on rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) reproduction, but contributes to the development of aphids with wings, which can transmit the virus more easily to new host plants. Additionally, symbiotic bacteria that live inside of the aphids can also alter aphid reproductive strategies based on the exposure to environmental stressors. In the autumn, host-alternating (heteroecious) aphid species produce a special winged generation that flies to different host plants for the sexual part of the life cycle. Flightless female and male sexual forms are produced and lay eggs. Some species such as Aphis fabae (black bean aphid), Metopolophium dirhodum (rose-grain aphid), Myzus persicae (peach-potato aphid), and Rhopalosiphum padi (bird cherry-oat aphid) are serious pests. They overwinter on primary hosts on trees or bushes; in summer, they migrate to their secondary host on a herbaceous plant, often a crop, then the gynoparae return to the tree in autumn. Another example is the soybean aphid (Aphis glycines). As fall approaches, the soybean plants begin to senesce from the bottom upwards. The aphids are forced upwards and start to produce winged forms, first females and later males, which fly off to the primary host, buckthorn. Here they mate and overwinter as eggs.

Sociality

Some aphids show some of the traits of eusociality, joining insects such as ants, bees, and termites. However, there are differences between these sexual social insects and the clonal aphids, which are all descended from a single female parthenogenetically and share an identical genome. About fifty species of aphid, scattered among the closely related, host-alternating lineages Eriosomatinae and Hormaphidinae, have some type of defensive morph. These are gall-creating species, with the colony living and feeding inside a gall that they form in the host’s tissues. Among the clonal population of these aphids, there may be several distinct morphs and this lays the foundation for a possible specialization of function, in this case, a defensive caste. The soldier morphs are mostly first and second instars with the third instar being involved in Eriosoma moriokense and only in Smythurodes betae are adult soldiers known. The hind legs of soldiers are clawed, heavily sclerotized and the stylets are robust making it possible to rupture and crush small predators. The larval soldiers are altruistic individuals, unable to advance to breeding adults but acting permanently in the interests of the colony. Another requirement for the development of sociality is provided by the gall, a colonial home to be defended by the soldiers. The soldiers of gall-forming aphids also carry out the job of cleaning the gall. The honeydew secreted by the aphids is coated in a powdery wax to form “liquid marbles” that the soldiers roll out of the gall through small orifices. Aphids that form closed galls use the plant’s vascular system for their plumbing: the inner surfaces of the galls are highly absorbent and wastes are absorbed and carried away by the plant.

See also

Aeroplankton Economic entomology Pineapple gall

External links

Aphids of southeastern U.S. woody ornamentals Acyrthosiphon pisum, MetaPathogen – facts, life cycle, life cycle image Sequenced Genome of Pea Aphid, Agricultural Research Service Insect Olfaction of Plant Odour: Colorado Potato Beetle and Aphid Studies Asian woolly hackberry aphid, Center for Invasive Species Research On the University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Featured Creatures website:

Aphis gossypii, melon or cotton aphid Aphis nerii, oleander aphid Hyadaphis coriandri, coriander aphid Longistigma caryae, giant bark aphid Myzus persicae, green peach aphid Sarucallis kahawaluokalani, crapemyrtle aphid Shivaphis celti, an Asian woolly hackberry aphid Toxoptera citricida, brown citrus aphid

Ancestry Graph

Further Information

„Aphidoidea“ on iNaturalist.org

Copyright

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Aphidoidea the free encyclopedia Wikipedia which is released under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License). On Wikipedia a list of authors is available.

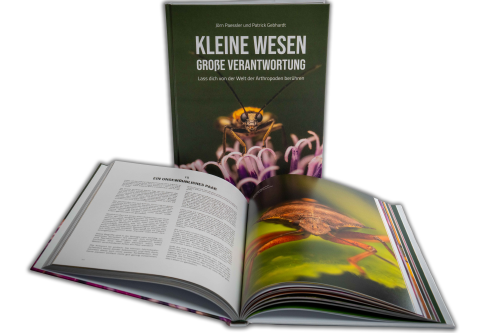

Little beings in print

Order our calendars and books today!

Compiled with love. Printed sustainably. Experience our little beings even more vividly in print. All our publications are available for a small donation.