Gastropods Lat. “Gastropoda“

The gastropods (/ˈɡæstroʊpɒdz/), more commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca, called Gastropoda. This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from the land. There are many thousands of species of sea snails and slugs, as well as freshwater snails, freshwater limpets, and land snails and slugs.

Hierarchy

Etymology

In the scientific literature, gastropods were described as “gasteropodes” by Georges Cuvier in 1795. The word gastropod comes from Greek γαστήρ (gastḗr ‘stomach’) and πούς (poús ‘foot’), a reference to the fact that the animal’s “foot” is positioned below its guts. The earlier name “univalve” means one valve (or shell), in contrast to bivalves, such as clams, which have two valves or shells.

Diversity

At all taxonomic levels, gastropods are second only to insects in terms of their diversity. Gastropods have the greatest numbers of named mollusk species. However, estimates of the total number of gastropod species vary widely, depending on cited sources. The number of gastropod species can be ascertained from estimates of the number of described species of Mollusca with accepted names: about 85,000 (minimum 50,000, maximum 120,000). But an estimate of the total number of Mollusca, including undescribed species, is about 240,000 species. The estimate of 85,000 mollusks includes 24,000 described species of terrestrial gastropods. Different estimates for aquatic gastropods (based on different sources) give about 30,000 species of marine gastropods, and about 5,000 species of freshwater and brackish gastropods. Many deep-sea species remain to be discovered, as only 0.0001% of the deep-sea floor has been studied biologically. The total number of living species of freshwater snails is about 4,000. Recently extinct species of gastropods (extinct since 1500) number 444, 18 species are now extinct in the wild (but still exist in captivity), and 69 species are “possibly extinct”. The number of prehistoric (fossil) species of gastropods is at least 15,000 species. In marine habitats, the continental slope and the continental rise are home to the highest diversity, while the continental shelf and abyssal depths have a low diversity of marine gastropods.

Habitat

Gastropods are found in a wide range of aquatic and terrestrial habitats, from deep ocean trenches to deserts. Some of the more familiar and better-known gastropods are terrestrial gastropods (the land snails and slugs). Some live in fresh water, but most named species of gastropods live in a marine environment. Gastropods have a worldwide distribution, from the near Arctic and Antarctic zones to the tropics. They have become adapted to almost every kind of existence on earth, having colonized nearly every available medium. In habitats where not enough calcium carbonate is available to build a really solid shell, such as on some acidic soils on land, various species of slugs occur, and also some snails with thin, translucent shells, mostly or entirely composed of the protein conchiolin. Snails such as Sphincterochila boissieri and Xerocrassa seetzeni have adapted to desert conditions. Other snails have adapted to an existence in ditches, near deepwater hydrothermal vents, in oceanic trenches 10,000 meters (6 miles) below the surface, the pounding surf of rocky shores, caves, and many other diverse areas. Gastropods can be accidentally transferred from one habitat to another by other animals, e.g. by birds.

Anatomy

Snails are distinguished by an anatomical process known as torsion, where the visceral mass of the animal rotates 180° to one side during development, such that the anus is situated more or less above the head. This process is unrelated to the coiling of the shell, which is a separate phenomenon. Torsion is present in all gastropods, but the opisthobranch gastropods are secondarily untorted to various degrees. Torsion occurs in two stages. The first, mechanistic stage is muscular, and the second is mutagenetic. The effects of torsion are primarily physiological. The organism develops by asymmetrical growth, with the majority of growth occurring on the left side. This leads to the loss of right-side anatomy that in most bilaterians is a duplicate of the left side anatomy. The essential feature of this asymmetry is that the anus generally lies to one side of the median plane. The gill-combs, the olfactory organs, the foot slime-gland, nephridia, and the auricle of the heart are single or at least are more developed on one side of the body than the other. Furthermore, there is only one genital orifice, which lies on the same side of the body as the anus. Furthermore, the anus becomes redirected to the same space as the head. This is speculated to have some evolutionary function, as prior to torsion, when retracting into the shell, first the posterior end would get pulled in, and then the anterior. Now, the front can be retracted more easily, perhaps suggesting a defensive purpose. Gastropods typically have a well-defined head with two or four sensory tentacles with eyes, and a ventral foot. The foremost division of the foot is called the propodium. Its function is to push away sediment as the snail crawls. The larval shell of a gastropod is called a protoconch.

Life cycle

Courtship is a part of the behavior of mating gastropods with some pulmonate families of land snails creating and utilizing love darts, the throwing of which have been identified as a form of sexual selection. The main aspects of the life cycle of gastropods include:

Egg laying and the eggs of gastropods The embryonic development of gastropods The larvae or larval stadium: some gastropods may be trochophore and/or veliger Estivation and hibernation (each of these are present in some gastropods only) The growth of gastropods Courtship and mating in gastropods: fertilization is internal or external according to the species. External fertilization is common in marine gastropods.

Feeding behavior

The diet of gastropods differs according to the group considered. Marine gastropods include some that are herbivores, detritus feeders, predatory carnivores, scavengers, parasites, and also a few ciliary feeders, in which the radula is reduced or absent. Land-dwelling species can chew up leaves, bark, fruit, fungi, and decomposing animals while marine species can scrape algae off the rocks on the seafloor. Certain species such as the Archaeogastropoda maintain horizontal rows of slender marginal teeth. In some species that have evolved into endoparasites, such as the eulimid Thyonicola doglieli, many of the standard gastropod features are strongly reduced or absent. A few sea slugs are herbivores and some are carnivores. The carnivorous habit is due to specialisation. Many gastropods have distinct dietary preferences and regularly occur in close association with their food species. Some predatory carnivorous gastropods include: cone shells, Testacella, Daudebardia, turrids, ghost slugs and others.

Genetics

Gastropods exhibit an important degree of variation in mitochondrial gene organization when compared to other animals. Main events of gene rearrangement occurred at the origin of Patellogastropoda and Heterobranchia, whereas fewer changes occurred between the ancestors of Vetigastropoda (only tRNAs D, C and N) and Caenogastropoda (a large single inversion, and translocations of the tRNAs D and N). Within Heterobranchia, gene order seems relatively conserved, and gene rearrangements are mostly related with transposition of tRNA genes.

Geological history and evolution

The first gastropods were exclusively marine, with the earliest known representatives appearing in the Late Cambrian (e.g., Chippewaella, Strepsodiscus). However, their only definitive gastropod feature is a coiled shell, which raises the possibility that they may belong to the stem lineage of gastropods, or might not be gastropods at all. Early Cambrian species such as Helcionella, Barskovia, and Scenella are no longer considered gastropods, and the small coiled Aldanella from the same period is probably not even a mollusk. It is not until the Ordovician that true crown-group gastropods appear. By this time, gastropods had diversified into a variety of forms and inhabited a range of aquatic environments. Fossil gastropods from the early Paleozoic are often poorly preserved, making identification difficult. However, the Silurian genus Poleumita contains at least 15 identified species. Overall, gastropods were less common in the Paleozoic than bivalves. Most Paleozoic gastropods belong to primitive groups, some of which still exist today. By the Carboniferous period, many gastropod shell shapes found in fossils resemble those of modern species, though most of these early forms are not directly related to living gastropods. It was during the Mesozoic era that the ancestors of many extant gastropods evolved. One of the earliest known terrestrial gastropods is Anthracopupa (or Maturipupa), found in the Carboniferous Coal Measures of Europe. However, land snails and their relatives were rare before the Cretaceous period. In Mesozoic rocks, gastropods become more common in the fossil record, with well-preserved shells. Fossils are found in ancient beds from both freshwater and marine environments. Notable examples include the Purbeck Marble of the Jurassic and the Sussex Marble of the early Cretaceous, both from southern England. These limestones contain abundant remains of the pond snail Viviparus. Cenozoic rocks yield vast numbers of gastropod fossils, many of which are closely related to modern species. The diversity of gastropods increased significantly at the start of this era, alongside that of bivalves. Certain trail-like markings preserved in ancient sedimentary rocks are thought to have been made by gastropods crawling over the soft mud and sand. Although these trace fossils are of debatable origin, some of them do resemble the trails made by living gastropods today. Gastropod fossils may sometimes be confused with ammonites or other shelled cephalopods. An example of this is Bellerophon from the limestones of the Carboniferous period in Europe, the shell of which is planispirally coiled and can be mistaken for the shell of a cephalopod. Gastropods also provide important evidence of faunal changes during the Pleistocene epoch, reflecting the impacts of advancing and retreating ice sheets.

Ecology and conservation

Many gastropod species face threats from habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change. Some species are endangered or have become extinct due to these factors. Conservation efforts often focus on protecting their habitats, especially in freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems.

Sources

This article incorporates CC-BY-2.0 text from the following source: Cunha, R. L.; Grande, C.; Zardoya, R. (2009). “Neogastropod phylogenetic relationships based on entire mitochondrial genomes”. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9: 210. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-210. PMC 2741453. PMID 19698157. Abbott, R. T. (1989): Compendium of Landshells. A color guide to more than 2,000 of the World’s Terrestrial Shells. 240 S., American Malacologists. Melbourne, Fl, Burlington, Ma. ISBN 0-915826-23-2 Abbott, R. T. & Dance, S. P. (1998): Compendium of Seashells. A full-color guide to more than 4,200 of the world’s marine shells. 413 S., Odyssey Publishing. El Cajon, Calif. ISBN 0-9661720-0-0 Parkinson, B., Hemmen, J. & Groh, K. (1987): Tropical Landshells of the World. 279 S., Verlag Christa Hemmen. Wiesbaden. ISBN 3-925919-00-7 Ponder, W. F. & Lindberg, D. R. (1997): Towards a phylogeny of gastropod molluscs: an analysis using morphological characters. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 119 83–265. Robin, A. (2008): Encyclopedia of Marine Gastropods. 480 S., Verlag ConchBooks. Hackenheim. ISBN 978-3-939767-09-1

External links

Gastropod reproductive behavior 2004 Linnean taxonomy of gastropods Webster, S.; Fiorito, G. (2001). “Socially guided behaviour in non-insect invertebrates”. Animal Cognition. 4 (2): 69. doi:10.1007/s100710100108. S2CID 25373798. – Article about social learning also in gastropods. Gastropod photo gallery, mostly fossils, a few modern shells A video of a crawling Garden Snail (Cornu aspersum), YouTube Grove, S.J. (2018). A Guide to the Seashells and other Marine Molluscs of Tasmania: Molluscs of Tasmania with images

Ancestry Graph

Further Information

„Gastropods“ on iNaturalist.org

Copyright

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Gastropoda the free encyclopedia Wikipedia which is released under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License). On Wikipedia a list of authors is available.

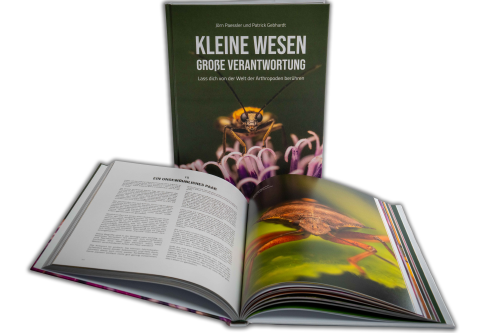

Little beings in print

Order our calendars and books today!

Compiled with love. Printed sustainably. Experience our little beings even more vividly in print. All our publications are available for a small donation.