The paradox of security

A tomcat and a female cat meet. And a spider secretly listens in. Satori, the tomcat, sits behind a glass pane and skeptically observes the balcony. The female cat, who depending on the time of day goes by Tricolor, Three-Colors, or Lucky Charm, lies outside on the warm stone slabs grooming her three-colored fur. Between them: a window pane, three centimeters thick, but really a whole world apart.

Theodora, the secret eavesdropper, withdraws deeper into her corner. She is a cross orbweaver. Eight legs, eight eyes, a body like brown velvet and leg hair so fine it can sense vibrations from three meters away. Garden cross spider – the name says it all: garden. Outside. Between rose bushes and raindrops. But Theodora has been living in Satori’s apartment for four years. More precisely: in the corner between the bookshelf full of Zen guides and manga mysteries, directly above the heater, where a perfect triangle of spider webs stretches. Right where Satori likes to sleep best, curled up between “Beginner’s Mind” and a volume of “Detective Conan.” She came through an open window on an autumn evening, when she was actually just seeking shelter from the first frost. Then she stayed. The warmth, the peace, the security – it was so much easier than outside.

“You live in a prison,” says Lucky Cat from outside. “Tricolor” today, because the neighbor just called her that, shortly after she had once again given their tomcat Brutus a piece of her mind. Satori, half Sacred Birman, half nobody-knows-exactly-what, with his ice-blue eyes, snorts disdainfully. “I live in safety. That’s a difference.”

“What safety?” asks Tricolor, her eyes flashing mischievously. “I bring my humans presents. Living presents. Yesterday a field mouse, the day before a shrew – the one with the pointed snout that shrieks so shrilly. I deposit them in the living room, meow loudly once to make sure everyone’s paying attention, and then?” She grins. “Then I lie down comfortably on my side and watch the spectacle. How they scream, wave brooms around, climb over furniture. Magnificent! All that’s missing is a bag of popcorn. And meanwhile, I’ve made it clear to fat Felix from number 12 that the backyard belongs to me. You? You get dry food from a bag.”

“Organic dry food,” Satori corrects. “Salmon flavor. Grain-free. Hypoallergenic.” Tricolor laughs a purring cat laugh. “Yesterday I had something the humans call squeeze-pâté. Pudding with cheese. From Bello’s bowl next door. It was wonderfully disgusting. Had to fight with Bello afterward, but it was worth it.”

Theodora knows both worlds. She is the border-crosser of this apartment – or should be, at least. Actually, she belongs outside, between morning dew and pollen dust, where her fellow species spin artistic orb webs between branches. Sometimes, when Satori dozes between his books, Theodora ventures out of her corner. Then she explores the sterile world of the apartment cat: The two-meter-high cat tree made of sisal that towers like a plush skyscraper in the living room – Satori only uses the lowest level. The water fountain with filter. The heated basket that Satori ignores because books are warmer. Everything clean, everything controlled, everything predictable. No surprises. No dangers. And unfortunately, few… flies.

That’s Theodora’s problem. In four years, she has caught exactly seventeen flies. Seventeen! Her cousin Brunhilde, who lived in the garden shed – where Theodora actually belongs too – caught that many on a good afternoon. But Brunhilde was eaten by a bird last winter. Theodora is still alive. That must mean something, right?

“You know,” says Tricolor, licking a paw, “yesterday I met a fox.” Satori sits up, his mismatched pair of eyes widening. “A real fox?”

“Are there fake ones?”

“And you’re still alive?”

“Obviously. I climbed a tree. The fox didn’t. End of story. Although the Russian Blue from across the street claims I screamed like a kitten from fear. Lies, of course. We’ve been enemies since.”

“Sounds like a hairy situation,” murmurs Satori and giggles.

Theodora thinks about trees. About enemies. About fights. She has never fought, only observed. Observed how Satori sharpens his claws on the scratching post in the morning – or rather: on the lowest board of the two-meter monster he was bought and which he calls the “skyscraper of missed opportunities.” Observed how he then pads to his favorite spot between the books, turns in a circle once, and falls asleep.

“I don’t understand you,” says Satori to Tricolor. “You could have a home. Warmth. Security. Regular meals. No territorial battles.”

“I have a home,” Tricolor counters, and her three colors shimmer proudly in the sun. “Several, actually. The Müller family feeds me in the morning, after I’m done with their Persian cat. The old lady from number 7 at noon, if I manage to get past her terrier. And in the evening, I stop by the döner shop, where I’ve fought for the best spot against three street cats. And in between…” She makes a sweeping gesture with her paw. “In between, the whole world belongs to me. Every square meter fought for.”

“The whole dangerous world,” Satori corrects, and his Birman heritage makes him appear dignified. “The whole living world,” Tricolor counters, showing her battle scar on her ear.

Theodora experienced something strange three days ago. A small fruit fly had strayed into the apartment. Instead of catching it, Theodora had observed it. The fly was panicked, repeatedly flying against the window pane, desperately searching for a way out. After two hours, it was dead – exhausted, dehydrated, trapped in perfection. Theodora hadn’t even eaten it. It felt wrong to eat something that had died from safety. She thought about herself – a garden spider that no longer knows any garden.

“Show me your web,” Tricolor suddenly says. Direct. Without beating around the bush. Just like she approaches her territorial fights. Theodora flinches. The spider has been discovered. “You can see me?” “Of course. You’re not exactly small. For a house spider. And I’m a lucky cat – we see everything. I even saw a ghost once. Was just the white cat from next door in the moonlight, though. Still – we have the seventh sense. Or as my buddy Tiger says: cat-tuition.” A self-satisfied grin.

“Garden cross spider,” Theodora automatically corrects. “I’m actually supposed to live outside.” Theodora leads the two to her web. It is, objectively speaking, a work of art. Perfect angles, even spacing, ideal tension. A web that couldn’t be better in any textbook. But it’s missing something – the morning dew, the pollen dust, the small leaves that get caught. The imperfection of nature. Tricolor observes it for a long time. “It’s dead,” she finally says. “Dead?” Theodora is indignant. “It’s perfect!”

“Exactly. When did you last renew it?” Theodora thinks. “About… two months ago?”

“See. My prey fights. My paths change. Every day a new opponent – this morning the Siamese cat, yesterday the Saint Bernard, tomorrow probably Brutus again. Your web stays the same because nothing changes in here. Outside, you’d have to spin it new every day – wind, rain, prey would destroy it.”

Satori jumps elegantly onto the windowsill, his supple nature showing in the unusual gracefulness. “Change is overrated. Stability is what counts.”

Theodora slowly climbs up her wall, past the book spines. From up here, she can see both cats. One, half Birman, half street, but completely house cat, lives between philosophy and fiction. The other, three-colored and battle-tested, carries every conflict of the neighborhood in her fur. Both are right. Both are wrong. And herself? A garden spider that has traded the garden for the heater.

“You know,” says Theodora, “I think the problem isn’t security or freedom. The problem is the illusion that you have to choose.” Tricolor tilts her head, one of her three colors glowing in the sun. “What do you mean?”

“Well,” Theodora begins spinning a new web. “Brunhilde is dead, but she lived. I’m alive, but have I lived? You, Tricolor, fight every day, but for what? And you, Satori, seek relaxation on books. We’ve all made choices – I chose the warm corner instead of the cold garden, you chose the street, he chose the apartment. We argue about opposites that perhaps aren’t opposites at all.”

“Philosophical spiders,” murmurs Tricolor. “Ones that actually belong in the garden, no less.” But she stays. And Satori stays too. They watch as Theodora weaves her new web. It’s different from the old one. More irregular.

Perhaps a bit more like the webs she would weave outside. If she dared. But that’s the point, thinks Theodora, as she pulls the last thread: Courage isn’t the absence of fear. It’s the decision to act despite the fear. And perhaps the greatest freedom begins exactly where you accept your own limits – and then gently shake them. Like a spider web in the wind that bends but doesn’t break. Tomorrow, she thinks, tomorrow I might venture to the windowsill.

A small step for a spider, but a giant leap for a cross orbweaver without a garden.

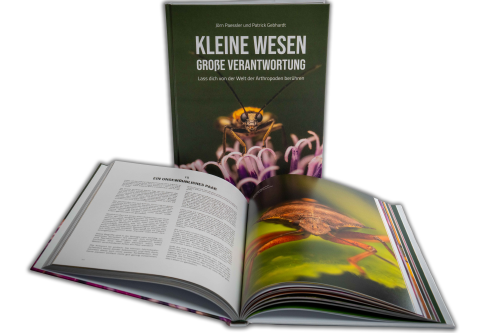

Little beings in print

Order our calendars and books today!

Compiled with love. Printed sustainably. Experience our little beings even more vividly in print. All our publications are available for a small donation.