Even sustainability can be staged

Ask Robert what he loves most about life, and he’ll say: “The ability to curl up and wait until the madness passes.” That’s not a figure of speech—he means it literally. In a world where even compost heaps are no longer safe, a hard-shelled “I’m outta here” maneuver is often the best option. His latest hiding spot? The right front wheel of a shopping cart. Cool, metallic, reliably rattling—a kind of cruise ship for ground dwellers. The plan is simple: short ride, hop off at the parking bay, back to the beloved blackberry bush. But as plans tend to do—they sometimes go their own way.

Pill bugs in the family Armadillidiidae are classics among European soil dwellers. For generations, Robert’s family has lived between rotting wood, fallen leaves, and occasionally a flower pot. Their bodies are dome-shaped, their antennae elegantly segmented, their uropods—the tiny plates at their rear—like miniature doorstoppers. And when things get dicey? Bam—ball mode. Not only does that ward off predators, it also helps in dry conditions. Robert can reduce water loss by up to 53% when rolled up. A walking climate solution, made by evolution.

His covert ride turns into a trap. As the cart is pushed through an automatic sliding door, Robert squints his compound eyes. It’s bright—sterile-bright, “lemon balm and lavender-bright.” And so his story begins—with a trip straight into the heart of an organic supermarket. And a pill bug who is horrified to find: between chia seeds, soy candles, and mountains of avocados, there’s sometimes a deep abyss. One called: performance.

The air smells of eucalyptus. He peeks out. Beneath him, the linoleum floor glows in biologically simulated beige. Shelves everywhere, perfectly lit, with labels that say things like fair, vegan, sustainable, climate neutral. Between the shelves: customers. Healthy-looking humans in linen trousers, most carrying cotton totes. They actually seem stressed. Still, they cradle their baskets with such care it’s as if they’re afraid of hurting the zucchini’s feelings. Robert crawls out of the wheel axle. It’s like someone ran his favorite compost heap through an Instagram filter. Everything gleams. Everything feels… curated.

First, he scuttles through the drink aisle. There he meets Gustav the earthworm, who had first landed in a net of identically shaped organic cucumbers and is now lost somewhere between Kombucha Ginger Dream and Oat Water with Aura. Gustav simply says, “I think I just need a real sip of soil.” Makes sense—who’d want to drink the water here? Glass bottles, labeled with mountains, springs, spiritual quotes. Sacred spring water from Switzerland—flown in, of course. The pill bug reads the label: CO₂-compensated. And wonders: how many trees does it take to offset half a liter of nonsense?

Robert hides beneath the shelf stocked with cricket-protein bars—and stares. There they are: Cricket Bites—the future of snacking, right next to organic snacks made from fava beans. Wrapped in glossy plastic with a matte eco-finish. Could it be more ironic? Crickets as ingredients—but heaven forbid they scurry through the store alive, or the exterminator gets called.

At the end of the refrigerated section, the pill bug is discovered by Eleonora—a fruit fly with a revolutionary mindset. She snuck into the organic store to protest long transport routes and excessive packaging. “That mango over there is from Peru! PERU! And wrapped in mint-scented plastic. This is insanity,” she hisses, buzzing angrily around the muesli bars with dried mango and spirulina. “They mean well,” says Robert. “And sometimes, that’s enough.” “No!” Eleonora shouts. “Good intentions don’t cut it when they’re staged under air conditioning and LED spotlights. Green is the new glossy!” Robert gets it. Between the organic grapes and the Himalayan salt for children’s feet, there’s little room left for real change. Everything feels like a theater performance.

He recalls something he overheard near the blackberry bush—a ladybug had mentioned an article from a major human newspaper: “The Organic Lie.” Apparently, some producers label conventional goods as organic, cram “organic” chickens into tight quarters, and claim it’s perfectly legal. Even certified eco-labels barely give hens enough room to raise their heads. Robert shakes his antennae. Sure, not every organic farm can be a utopia—but if sustainability itself becomes a label that bends like a limp celery stalk, then something’s gone seriously wrong.

The peak irony comes at the checkout. There’s a sign: We love our environment. Please buy our cotton bags – only €5.90! Next to it: a display of tiny plants in jars. Urban gardening for your desk. Robert crawls closer: quartz sand, plastic lid, seeds in cellophane. A houseplant that will never grow—but looks cute. “You know,” says Eleonora, “sometimes I think this whole place is like a terrarium. Warm, green, controlled on the inside—but outside, real life rages on. Droughts, species loss, waste. In here, people feel good because they buy almond milk and coconut cream. But out there, not much changes.” Robert nods. He thinks of the compost behind the blackberry bush. Dirty, yes. Chaotic, too. But honest. No labels, no marketing slogans. Just processes. Change. Decay and emergence.

At the exit stands a mirror with the words: You are part of the solution. Robert stares into it skeptically, sees himself—a grey-brown, armored little thing. Not part of the performance, but part of the whole. A quiet recycler. A returner. A realist. He curls up again—not out of fear, but out of defiance. And as the cart is wheeled back outside, he gratefully rolls out—out of the world of creative labels, back into the world of real cycles.

Later, back at the blackberry bush, Robert recounts his unintentional excursion. One of the snails just nods and says, “Figures. My grandma always said: if it’s shiny, it’s rarely good for the soil.” And as the others gather around a mushy apple slice and bite in with gusto, Robert thinks: maybe true sustainability is exactly that—quiet, humble, unphotogenic. But damn important.

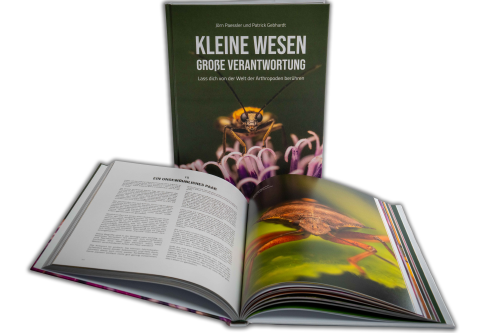

Little beings in print

Order our calendars and books today!

Compiled with love. Printed sustainably. Experience our little beings even more vividly in print. All our publications are available for a small donation.