The old man and the Chorthippus apricarius

“I think I’m gradually… becoming unheard,” murmurs Fridolin, twitching a hind leg. It’s midday, and the sun blazes down on the withered grass along the railway embankment like a diligent grill master. Perfect weather for the Chorthippus apricarius — that’s what science calls him. To himself, he’s simply Fridolin: grasshopper, male, medium-sized, brown with greenish speckles, about 15 millimetres of pure temperament on six legs. Fridolin is a singer. No loudspeaker, no stage hog, more like… “Tick — schrrr — schrrr, tick — schrrr — schrrr.” Anyone who knows his song understands: nothing is random, everything is intentional. A signal meant to attract females, keep rivals away, and soothe the mind. Provided, of course, that someone hears it.

But Fridolin’s song, once clearly audible within a ten-metre radius, is now drowned out by the madness of the world. A leaf blower roars two gardens away, a jackhammer pounds in sync with a nervous city, a bus squeals around the corner. Fridolin starts a verse, hesitantly, as always: “Tick — schrrr — schrrr…” A dog barks, drowning out everything. The grasshopper collapses like a tired daisy. For days, no female has responded to his stanzas. Perhaps his rhythm has gone out of fashion. Perhaps everything else is too loud. Or perhaps the world’s hearing is simply… broken.

Standing on a withered blade of grass, he gazes at the residential building at the foot of the embankment and sighs. Concrete, cars, air conditioners. Like all grasshoppers, even a Chorthippus apricarius prefers the comfort of grass blades over house walls. And yet: something unusual happens on the third balcony from the left. An elderly man sits there every midday on a stool. He barely moves. Only a glass of water sits beside him. He is thin, almost transparent, wearing headphones around his neck instead of over his ears — and again and again, he pauses. As if he’s… listening?

Fridolin hops closer, across a power line and an ivy vine, finally landing on the railing. The man looks up. “Well, hello there, little locomotive driver,” he murmurs. Fridolin freezes. “Heard you yesterday already. Just briefly. You sound like an old locomotive. Tick, schrrr, schrrr. Haven’t heard that in years. At first, I thought it was in my ear.” The man smiles wryly. “Tinnitus. An endless ringing. But your sounds were different.” Fridolin vibrates slightly with excitement. No human had ever praised his song before. Most either hear nothing — or just “noise disturbance.”

From that day on, Fridolin visits the balcony daily. The man — his name is Ernst — starts paying attention to him. He sets up a small microphone connected to an old recording device. Fridolin’s song is preserved, analysed, even played back. “You know,” says Ernst, “my audiologist says I should avoid sounds. But your rhythm… it calms me. Brings order to the noise in my head. I even slept again.” Fridolin doesn’t understand a word. But he senses that his sounds are having an effect.

Over time, a kind of familiarity develops between Ernst and Fridolin. Not planned, not orchestrated — it simply exists. No training, no taming — more like a quiet agreement. Fridolin starts singing as soon as the sun moves across the south-facing balcony. And Ernst listens. Without headphones, but with an open ear. Eventually, Ernst hangs a small sign on the railing: “Sound Island — Please do not disturb. Nature sings here.” Ernst tells others about it. First the neighbours, then his old choir, and finally a local journalist. “A Grasshopper Heals My Hearing,” headlines an article found on the S-Bahn between ads for shower gel and hearing aids.

A young biologist stops by, listens to Fridolin, and simply says: Chorthippus apricarius! Typical for railway embankments. Acoustically unmistakable. And: endangered in some regions. Fridolin’s song is recorded and added to a digital archive of insect sounds. There he now hums among other voices. A locomotive — just a few minutes long, a few stanzas, each one proof that it exists: peace in the chirping. A small-scale symphony.

One evening, as the sun hangs particularly low, Fridolin wonders: Am I actually important? Of course, he receives no answer. Not from Ernst. Not directly. But the microphone is on. And Ernst simply sits there, motionless, eyes closed — not asleep, but listening, as if he has found the sound within himself. And while city traffic flickers, sirens wail, and somewhere a leaf blower roars, Fridolin sits atop the blossom of a wild carrot, raises his leg — and sings. Down on the sidewalk, two people pause. “Do you hear that?” one asks. “Sounds like a steam locomotive, doesn’t it?” “Yeah… haven’t heard that in a long time.”

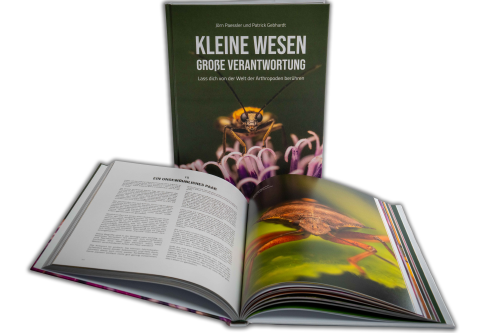

Little beings in print

Order our calendars and books today!

Compiled with love. Printed sustainably. Experience our little beings even more vividly in print. All our publications are available for a small donation.